Composing a response speech (rebuttal) on the fly in the middle of a debate round is a daunting task, yet not completely impossible. It takes time, practice, and experience across multiple tournaments. Eventually, almost every debater gets well-acquainted with making this speech and is able to speak as if they had prepared. This section will cover what is recommended for an organized and structured rebuttal.

Rebuttals are speeches that briefly extend and rebuild your case (by addressing your opponent’s attacks), while also attacking your opponent’s case. This means NO NEW ARGUMENTS – only responses to the original constructive case and responses to these responses. For example, if you and your opponent ONLY talked about climate change and nuclear war in your constructives, there shouldn’t be the introduction of a new contention (e.g. with the impact of bioterror / pandemic) in the rebuttals that follow.

But you gotta applaud them for fitting 5 contentions into 4 minutes of speech

Whereas a constructive speech is written entirely before the round starts, a rebuttal is adjusted to what your opponent just presented within the round. Therefore, it is more difficult with the time limits and pressure. There are several rebuttal speeches throughout the round, including the 1NR (rebuttal section of the Neg constructive), 1AR, 2NR, and 2AR. More than half of the debate is spent either preparing for or delivering rebuttal speeches.

Before we jump directly to rebuttals, it is important to introduce the basic types of arguments and types of responses that you will be utilizing in your speeches.

Offense and Defense

Arguments that both Aff and Neg present in debate, whether a contention or a response, can be categorized under offense or defense (just like in sports). Offensive arguments are reasons that you should win (why the judge should vote for you), e.g. the contentions you present in your constructive case. Defensive arguments are reasons why you shouldn’t lose (why the judge shouldn’t vote for your opponent).

Think of these two argument types in comparison to sports: offense and defense are both necessary to win any game. In soccer, you need your goalkeeper and defenders, as well as offensive players like strikers. Having purely defense will at best get you a 0-0 tie. Meanwhile, with only offensive plays, you would have to struggle a whole lot in order to purely out-score the other team, although winning here is possible.

Comparing these extremes in a debate context, having zero defense but a bunch of offense means that you might just win, as there are reasons to vote for you, although it would be quite difficult to do so. But on the other hand, having zero offense and 100% defense is not sufficient to win, as you are only proving to your judge that they shouldn’t vote AGAINST you: there aren’t actual reasons to vote FOR you. This doesn’t mean that you should only focus on offense: both types of arguments are important to helping you win.

Examples of pieces of offense are contentions: they’re reasons why your position is good and why you should win, compared to your opponent. Examples of defense are included among the types of responses, which brings us to…

Responses

Recalling our “claim, warrant, impact” or “resolution -> links -> impact” structure of argumentation, what happens when your opponent presents their well-crafted and indestructible contentions? How do you even attempt to demolish such a seemingly lofty structure? This is where offensive and defensive responses come into play: defense preventing your opponent from winning, and offense actively telling them that they should lose because they do something bad. These attack your opponent’s contention link(s) and/or impact(s). A useful analogy is thinking of this process as preventing your opponent from finishing a race, or driving from point A to B. The claim/resolution is the start line (point A), the link is the course or road in between, and the impact is the finish line (point B, endpoint). There are multiple ways to sabotage them:

- Defense: Try to destroy sections of the road (delinking),

- Defense: Tell them that their trip was not unique, worthless, or that there’s no “finish line” in the first place – BIG emotional damage (impact mitigation),

- Offense: Turn the road around and trick them into going the opposite direction or somewhere else off-course (link turn), and

- Offense: Telling them that their journey wasn’t a good thing in the first place (impact turn).

Note that it is absolutely recommended to build your CONSTRUCTIVE case out of purely cards / cited evidence. But on the other hand, it is common for a REBUTTAL to be made up of plain old speaking and logic, known as “analytics“, where you just structure your points as if you normally would speak outside of debate (rather than formatting everything into a card), due to having to do rebuttals on the fly. Although you should present your spoken points / responses in a structured order (explained near the bottom of this page), using cards is uncommon. Note as well that for SOME responses (particularly those addressing really strong contentions), having them in the form of CARDS / cited evidence is ideal to be able to combat your opponent’s credible evidence with credible evidence of your own. Whether to use cards or not in your rebuttal – this decision ultimately depends on your preferences, as well as how much time you have in your speech. For clarification, AVOID CUTTING CARDS IN-ROUND: just read stuff that you prepared beforehand (e.g. cards that you cut before the tournament, anticipating your opponent’s case/responses).

Now, on to the subcategories of responses…

Defensive Responses (Takeouts)

Defensive responses, a.k.a. takeouts, are common yet effective ways to prevent your opponent’s contentions from mattering. The goal is to take out their contention and make it no longer matter in the debate, hence eliminating a reason for the judge to vote for your opponent (rather than creating a reason to vote for you, as offense would). The two main takeouts are delink and impact mitigation arguments.

Delink (a.k.a. “no link“): this attacks a specific link in the story of your opponent’s contention. Delinks say that the link they described is actually FALSE, therefore causing the rest of their contention (including the REALLY TERRIFYING impact) to not happen at all and not affect the debate.

Take the example of a general, hypothetical Neg case on a topic about UBI in the United States, or Universal Basic Income (you’re arguing for the Affirmative). For context, Aff would say that everyone deserves a specific base amount of income, regardless of being poor or rich, employed or not. Neg disagrees:

- Connection/link to the topic: There is currently no Universal Basic Income in the U.S., but the Aff’s proposal of a UBI would waste vital resources and money.

- Link 1: The funds spent on UBI could instead be used by the federal government to invest in businesses to stimulate the economy and keep it from another big recession, especially during a pandemic (e.g. COVID).

- Link 2: Recessions cause political leaders to take drastic action to ensure that they remain in power or are still popular among voters, thus compelling the President of the U.S. to go to war with China more willingly. A small event, like a skirmish over Taiwan, could provoke a full-scale conflict.

- Impact: In the end, the U.S. and China will exchange nukes, which destroy the planet and humanity along with it. All because we allowed for a Universal Basic Income.

If the Aff were to respond to this contention by delinking, they could target any of the links (link to the topic, Link 1, and Link 2). Let’s use Link 1 for example: Aff could take down the Neg’s claim about businesses and the economy needing financial stimulation – maybe the economy is doing fine right now, and it won’t enter a recession even if the government doesn’t fund businesses (no recession = no war = no extinction). These delink arguments prove a single link to be false, and because your opponent depends on every single link to access their ultimate impact, they can’t win the contention, even if only one link is taken out.

Impact mitigation (a.k.a. “impact defense“, or “no impact” argument): this argument takes out the end impact, rather than the link(s) in between. It says that the Neg’s claims about their impact are false. There are multiple types of impact mitigation:

- The impact doesn’t do anything / there is no impact (the UBI example: sure, China-U.S. tensions may rise, but nuclear war is impossible),

- The impact isn’t as bad as it is said to be by your opponent (e.g. China-U.S. war will at its worst be a few missile exchanges offshore near the mainland, but nothing nuclear, unlike what the Neg claimed),

- The impact is non-unique (the impact of war happens either way / is the same, whether you vote for Aff or Neg, because China and the U.S. are already very willing to fight each other).

It is usually best to do impact mitigation ALONGSIDE an argument putting offense/defense on their link(s). It’s like an even-if statement: “even if you manage to prove my delink false, your impact in the end doesn’t matter.” This enables a stronger attack on your opponent’s case.

When your opponent doesn’t answer defensive link/impact arguments, their whole contention is effectively taken out – they can no longer use this contention as it is PROVEN FALSE. Your job afterwards is to mention the same defensive arguments in your next speech (as well as the fact they dropped them), so that it is clear to the judge that this contention should no longer be factored into the end decision. A.k.a. your opponent can’t win anymore by depending on this contention! But then again, they can focus on their second or third contention(s), which may still be in play and not yet dropped. So the question is: how do you give your opponent a harder time answering your attacks? This is where offensive turns come in…

Offensive Responses (Turns)

Using your opponent’s arguments against them is also known as “turning” or “turns“. The cool and strategic thing with turns is that, unlike defensive takeouts, your opponent MUST address these responses or else they could lose the round due to them (thus, turns are an offensive form of argumentation).

Link turn: this states that the opposite of their link is true. Therefore, they either cause their own impact, or you are able to solve their impact better than they do. This turns their whole contention around and serves as offense, a reason that the judge should vote for you!

With the UBI example, Neg’s Link 1 states that government funding for businesses is necessary in order to keep the economy afloat. A delink says that the economy is fine right now. But a link turn might say that a basic income for everyone means the people themselves and regular everyday consumers stimulate the economy with their new income and ability to spend more on the products of these businesses. Instead of the government just paying businesses directly (in which the funding might only go towards the salaries of big CEOs like Jeff Bezos), a UBI allows the public to stimulate the businesses, and hence the economy. Therefore, the Aff allowing for UBI in fact does a better job than the Negative at helping the economy. The story doesn’t end there: because the Neg fails at preventing recession, they themselves will cause the nuclear war they mentioned. Meanwhile, the Aff can prevent nuclear war through UBI.

Impact turn: saying that the impact is GOOD. Is your opponent trying to prevent nuclear war from happening? Impact turning would say that “nuclear war = good”. You can already tell that this argument is a spicy wildcard. Think of it lightheartedly as “turn that frown upside down”.

Notice that when attacking the link with delinking or link-turning, you’re still saying that climate change or nuke war is 100% bad and should be prevented. But on the other hand, impact turns COMPLETELY turn the tables and claim that “climate change = good” or “let’s go, nuclear war”. The reason that this might be strategic is when your opponent does a bunch of work on the link chain/story leading up to their impact, and leave their impact open for criticism. When reading impact turns, it’s best to just concede and agree to your opponent’s links (don’t use delinks or link turns) – the stronger their links, the better.

Caution: (depending on your area) many judges don’t think impact turns make sense / believe that they are quite extreme, since the end implication of nuke war and climate impact turns is that “extinction = good”, because we get a “fresh restart for humanity” or that humanity is evil for polluting/killing animals in the first place. Among the list of other (usually not utilitarianism framework) impacts you can turn are capitalism, American hegemony / power, securitization (fearmongering), and liberalism.

Meanwhile, WHAT YOU DON’T WANT TO IMPACT TURN (this is a serious warning about what to 100% never ever impact turn): structural violence impacts, racism, ableism, etc other types of impacts about the real oppression of minorities and marginalized groups. Do not say that these are good things. Opponents, judges, and tournament organizers will not appreciate this. These specific turns are round-losing arguments – there is no place in debate to allow speeches that downplay the seriousness of racism / homophobia / oppression, let alone spinning these issues (that affect and harm people every day) for the good.

Meanwhile, when going for acceptable impact turns, watch out for double turns or double-turning yourself (this isn’t very strategic). This occurs when you read both a link turn AND an impact turn. The problem is that when you say “I prevent nuclear war from happening” and “nuclear war = good”, the logic goes that you are preventing a good thing from happening. Your opponent just has to concede the two turns, say that you’re double-turning yourself, and you likely will lose. Same thing visa versa: you should call out your opponent when they make double turns and emphasize clearly to the judge that they should be basing their decision on this.

In general, link turns and delinking are the most commonly used types of responses: you should be using them as much as possible, given that they don’t contradict other types of arguments. Be careful when making multiple responses with delinking and link-turning at the same time. If your opponent isn’t planning on extending that particular contention, they can strategically concede to a delink argument and move on, abandoning their own contention altogether. This may be a smart move by them to trade off on time – for example, take a situation where you spent 1 minute reading turns and delinks, while they just used 10 seconds to concede and move on. Using that extra 50 seconds, they could fortify their other offense and contentions better. Think of it like strategically sacrificing pieces in chess: your opponent sacrifices a pawn (the contention), in order to take your queen (your time, and over the duration of the round, the time you have to respond to their other contentions). Therefore, usually 3 in-depth, high-quality responses per contention are plenty enough.

A similar thing goes for the link turn + impact defense combination: your opponent can just concede that they cause an unimportant impact to happen, or that you solve for a non-existent impact, and move on.

Responses to Responses – Answering Your Opponent’s Attacks

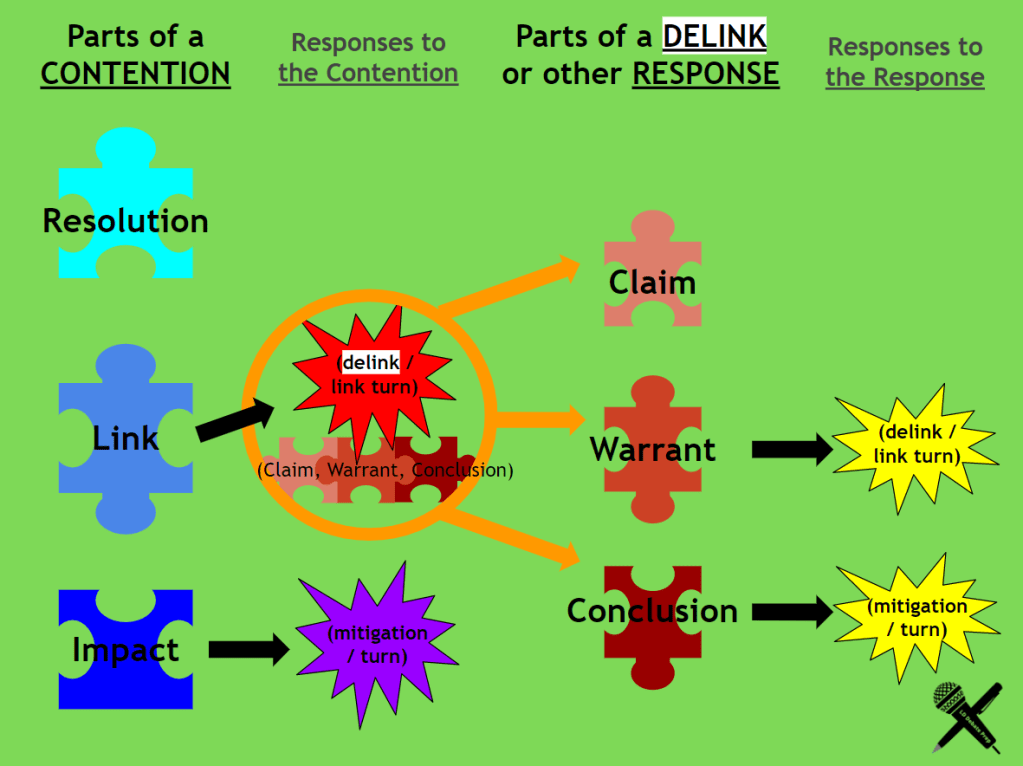

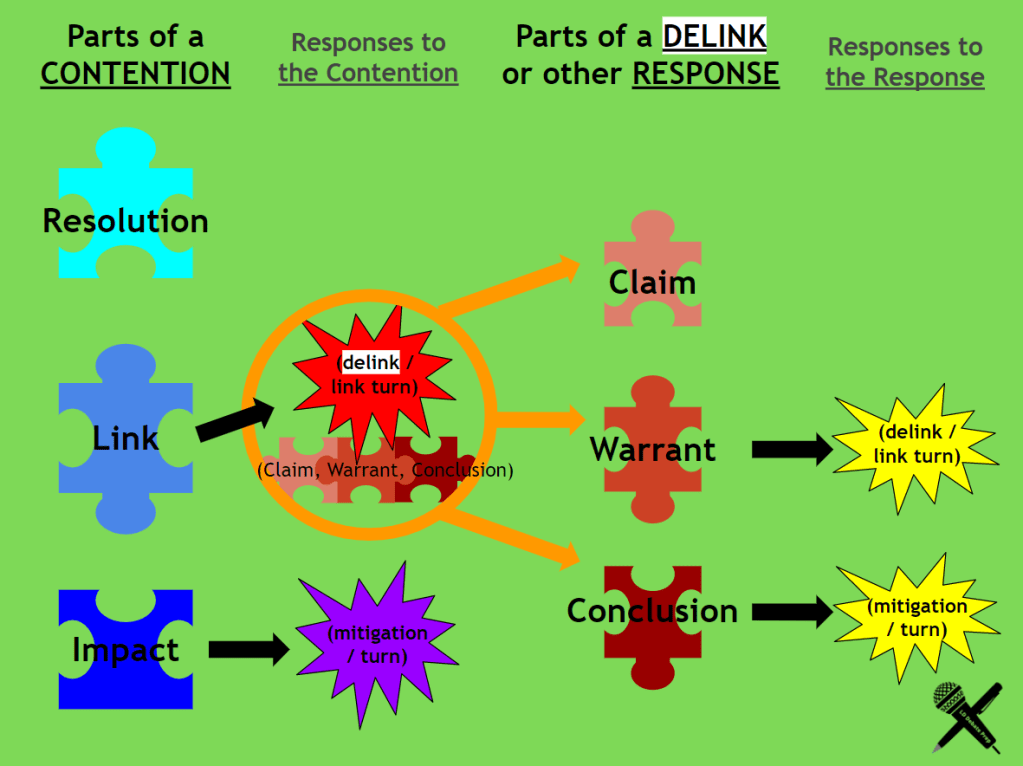

Once again referring to a contention’s structure of “claim, warrant, impact“ / “resolution -> links -> impact“, we can apply it on a smaller scale and onto the general structure of a response (turn or takeout, mentioned in the previous section). Whereas responses break down a contention into individual parts and address them one by one, this section of the page will talk about how to break down those very responses into simple parts, in order to then respond to those responses.

Note #1: we will be using the sub-structure of a response ONLY in this lesson, so try to hold on to this train of thought. Beyond this Responses to Responses section of the lesson, “delink” / “impact mitigation” / “link turn” / “impact turn” will ALWAYS refer to the contention level.

The orange circle + arrows surrounding “delink” show how the delink itself is broken down into its basic components – claim, warrant, and conclusion.

Note #2: Instead of using the term “impact” to describe the end result of a response, the word “conclusion” is a more accurate term, as e.g. your contention link (which your opponent is responding to) doesn’t have an end impact, but rather a temporary conclusion for the NEXT link / end impact to pick up where it left off at.

Referring to the diagram above, this section will focus on the yellow bubbles with the jagged/spiked edges, labelled “delink / link turn” and (conclusion) “mitigation / turn”.

Defensive and offensive responses can be made on a smaller scale when responding to the responses of your opponent – swatting down their attacks on your case. In short, you can say that their claim is false (takeout), what you do is good (turn), or that their statement doesn’t matter (non-uniqueness takeout).

(Moving away from the UBI example to a more general one). A common argument across all topics, in the form of a delink or link turn, is for your opponent to claim that your contention harms businesses (big, small, or all businesses in general). Here are the main ways you could respond to your opponent’s response, via “mini” versions of delinking, impact (conclusion) mitigation, link turn, impact (conclusion) turn, and non-uniqueness claiming:

Delink the response: you could read a piece of evidence that proves you DON’T harm businesses.

Mitigate the impact/”conclusion” of the response: you might say that your contention doesn’t harm businesses all that much – it’s not enough to drastically affect their operations.

Link turn: you could read a piece of evidence that NOT ONLY proves you don’t harm businesses, but instead BENEFIT them with your contention (and/or say that your opponent in fact hurts businesses).

“Conclusion” turn: maybe limiting the power of big corporations like Facebook and Amazon is a good thing, in order to e.g. protect the privacy of citizens / app users, or ensure safe working conditions for workers in warehouses.

Non-uniqueness takeout: you may point out that businesses will be harmed no matter what, whether we vote for the Aff or Neg. Therefore, it wouldn’t be productive to further debate about it since we know that businesses being harmed is an inevitable fact.

Weighing

In every util vs util debate, both sides are trying to win their impacts under utilitarianism. The Aff and Neg are FIGHTING to convince the judge that their impact is the BIGGEST, BADDEST, and MOST LIKELY one to occur. Think of this process as weighing two items (the impacts) on a balance or scale – you want your impact, whether it’s climate change or nuclear war, to be worth MORE than your opponent’s (a.k.a. your judge values preventing your super scary impact over your opponent’s). This is where the terms “weighing” and “outweighing” come in.

“Weighing” (a.k.a. “impact weighing” or “impact calculus“) refers to the comparing of your impact against your opponent’s impact. This is a vital part to debate, near the end of your rebuttals (namely the 2NR or 2AR).

Meanwhile, to “outweigh” means to win your impact. “Climate change outweighs nuke war” is to say that the impact of climate change is more important to address and prevent than nuclear war. Outweighing serves mainly as offense – why your impact should win compared to your opponent’s, and why you should win the round overall. In order to outweigh, there are a couple of main metrics or measurements of weighing that you will use:

- Timeframe – How urgent is it to address the impact? How soon will the impact happen?

Example: Nuclear war may outweigh climate change on timeframe, as a global launching of nukes will destroy humanity in a few days, whereas climate change is the slow heating up of the Earth over decades. - Probability – How likely is the impact going to occur?

Example: Climate change outweighs nuclear war on probability. Climate change is happening right now and evidence proves that it will for sure continue happening, unless we address it. Meanwhile, nuclear war is an unlikely possibility, as world leaders are likely very cautious about the upfront use of weapons of mass destruction. - Scope – How many people will be affected by the impact?

Example: The emergence of a new deadly disease outweighs nuclear war in terms of scope. A global pandemic spreads through communication and transportation networks in today’s heavily interconnected world, ensuring that every person on Earth is affected. Meanwhile, the launching of nukes will only affect people living in major population centers / cities. - Magnitude – How bad or severe is the impact (in terms of the effect on individual human wellbeing or living conditions)?

Example: A deadly disease pandemic outweighs AI (robot) revolution on magnitude. A global pandemic would create economic hardships, job losses, starvation, and eventually the slow torturous death of humanity. On the other hand, instantaneous extinction at the hands of robots and autonomous weapons is less painful. - Reversibility – Is the impact reversible?

Example: Climate change is harder to reverse (possibly irreversible), compared to a collapsing economy. A warming planet will eventually become uninhabitable for humans, while economies have entered depressions or recessions many times throughout history yet people have been able to overcome these hardships in the long run.

Usually using for 2 out of the 5 weighing metrics in one round is good enough. Too many could be a waste of time.

Make sure to contest your opponent’s weighing metrics as well! You likely will have to weigh between weighing metrics, so be prepared to justify why (for example) probability is a better way to evaluate an impact than magnitude (we should focus on preventing something we know for certain will happen), or how a shorter timeframe requires prioritization above probability (only through ensuring humanity’s survival in the short term can we address other problems in the future).

In summary, ALWAYS WEIGH IMPACTS!!! This is your key to convincing the judge to vote for you in a util debate.

Putting It All Together (The General Rebuttal Structure)

As a refresher with some definitions from the Speech Order lesson, to “extend” means to reinforce the arguments you presented in your constructive speech. This involves summarizing your case or a specific contention in order for the judge to consider it in their evaluation at the end round.

But also be careful with “dropping” or “conceding“ or “kicking” parts of your case! These terms mean failure to respond to a definition, framework, or contention (whether intentionally or unintentionally), although “kicking” usually refers to a more purposeful / strategic dropping of part(s) of your case. We will get to that soon, because now is the time that you put EVERYTHING together to form a coherent rebuttal speech!

In every rebuttal speech (both Aff and Neg), there are different strategies associated with them, which represent their overall relevancy to the round as a whole:

- 1NR (in/after the 1NC): the Neg just does base-level responding to the Aff case, in a sense introducing arguments with an emphasis on quantity over quality. This rebuttal speech is just an addition to the Neg constructive (1NC), therefore it only responds to the Aff case (no extending of the Neg case needed).

- 1AR: the goal of this speech is to maximize the possible “outs” or possibilities for winning by the time the Aff presents the 2AR (the speech after the 2NR). This usually involves extending a single contention in-depth, responding to Neg’s responses associated with the Aff contentions, and putting work into addressing Neg’s contentions.

- 2NR: this speech is the Neg’s key to winning the debate. Neg debaters must respond to the 1AR and prevent all possible “outs” for the 2AR. Basically the same structure of the 1AR, but with 6 minutes of time instead of 4.

- 2AR: The Aff zooms in on describing one (or two) round-winning factors that will deliver the win to them. This is the Aff’s moment to have the final say and try to convince the judge to vote for them. This involves continuing to extend 1 argument and responding to strong Neg points made in the previous 2NR or throughout the debate.

Because the 1NR and 2AR are relatively easier to understand, we will be focusing in on 1AR and 2NR structure (they’re relatively the same, just with a difference in time/minutes).

Structure – 1AR & 2NR (First Aff & Second Neg Rebuttal Speeches)

- Overview: this is a 10-15 second statement or summary on what is the most important issue(s) in the round. It basically opens your speech with a BANG and reveals to the judge why they should be voting for you!

- Extend your framework / address the framework debate: these are justifications for why the framework you are using is good. If you and your opponent both agree on the framework (e.g. util), you may just move on. On the other hand, if you both heavily disagree (e.g. util vs Kant, an ethics-based philosopher), the framework debate will take up the majority of the time, thus putting aside contentions and mostly focusing on interactions between the different philosophies. For our purposes right now, we will be describing what a rebuttal would look like when you and your opponent agree on a utilitarian framework.

- Extend ONE of your contentions, while responding to responses: extend / re-explain one of your strongest (or least-contested) contentions. This involves a clarification on the link story and impact, which may take half of your speech (or at high efficiency, 30 seconds to 1 minute). Make sure to respond to all your opponent’s responses/attacks in the order they were presented (this is called line by lining, or LBL), addressing turns and takeouts either as you extend your contention or after you do so.

Kicking in the 1AR and 2NR is strategic for focusing on a single contention, hence putting quality explanation and rebuilding into a shorter amount of time. If you have multiple contentions and are just extending one, remember to indicate that you are kicking the other one(s). If you are keeping contention 1 (C1) and kicking contention 2 (C2), you have to answer all the turns that your opponent put on C2 first. This is because turns are offensive arguments – when unaddressed, they will help your opponent win the round.

Another note: It is important to ALWAYS extend your own case first. I cannot stress how necessary this is, as I have lost multiple rounds by going all-in on answering my opponent’s case first (mostly defense), eventually forgetting the clock and running out of time to rebuild my own case (offense). Remember that you can win without defense, but you will always lose if you don’t uphold your offense, a.k.a. your contention(s). If you do not re-explain and address responses made on your case, you have effectively dropped your offense. - Move on to opponent’s case: time to attack / respond to your opponent’s contentions! Much the same with line by lining their responses previously when rebuilding your own case, here is where you introduce turns, impact mitigation, and link defense to their contentions (in the order they presented the links & impacts, of course). If they have decided to kick an argument, usually you can just ignore it and move on. But in the case they kicked it without sufficiently answering a turn you made on it, you can hammer in the turn (in your 2NR or 2AR) and try to make this a key issue of the round for the judge to consider, because your opponent basically conceded / insufficiently covered a piece of your offense.

- (optional, only for 2NR and 2AR) Summary / voters: recall that voters are 2-3 points that summarize reasons why you win, at the end of your very last speech (the 2NR or 2AR). This is not absolutely required for you to win the round, but summarizing does help with your perceptual advantage/credibility and helps the judge to understand your arguments better (in the worst case that they have been sleeping the whole round until you summarized the round). Usually, you want to slow down, speak slightly louder, and emphasize that “look, judge, these are the 3 reasons why you’re going to be voting for me today…”. These reasons are short and sweet, yet have big implications in-round. They can range anywhere from your opponent dropping entire contentions, to the fact that you are winning your framework, to your impact mattering more under impact calculus (weighing impacts). In util debates, two of your voters could be the fact that your impact (climate change) outweighs your opponent’s (nuke war) based on both probability and magnitude.

In conclusion, with anything major that your opponent dropped (whether it be a link turn, impact defense, other response, or perhaps a whole contention), make sure to point this out loud and proud to the judge so that they are aware of the potential implications (basically, what you said remains true because it is uncontested in the round, thus your opponent should lose). On the other hand, try not to drop anything that could spell the end of the round for you (e.g. turns, every single one of your contentions (except when kicking), etc).

The art of the rebuttal takes practice to master. The best way to improve is to do it hands-on. Now you know the concepts, go deliver some round-winning speeches!