Despite the freedom in running various perspectives of argumentation, debaters still need to take into account the background of their audience if they wish to win the round. After all, your judge is the one who needs to be convinced to vote for your contentions; you’re not there to change your opponent’s mind. Therefore, a key aspect of debate is judge adaptation, or making arguments based on what your judge can understand and tolerate, because judges are the ones deciding who wins the round. A judge’s philosophy is a key component that guides the strategy of argumentation a debater wishes to pursue in the round. Failing to account for such changes may lead to a lost round.

A judge’s philosophy can be seen in their paradigm, which is a written description with a few paragraphs – detailing what they evaluate and how they tend to evaluate debates. A paradigm’s primary purpose is for debaters to get an idea of their judge before the round starts, so always read your judge’s paradigm in the few minutes between rounds! Paradigms usually will list things like the judge’s background (coach, former debater, beginner judge, etc), what speed or rate of speaking the judge can tolerate, and other specifics in terms of argumentation. Additionally, a full list of their judging record can be seen, including specific rounds and how long they have judged for.

But some judges may not have written paradigms (e.g. because they’re new, they forgot, or there’s an error with the system). Whatever the reason for a missing paradigm, or even if there are parts of an existing paradigm that are confusing to you, you should ask clarifying questions on how they judge when you see them before the round starts. For example:

- What do they generally hope to see debaters do in the round?

- How do they factor cross-examination into the debate?

- What is their opinion on advanced arguments like kritiks? (kritiks fully explained in a later unit)

Overall good things to do (during the debate) in front of all judges include:

- Giving empirical / real life examples of proof for your contention. This can just be an analytic brought up during your rebuttal, not necessarily in carded format as a part of your constructive;

- Having an idea of the general debate and who is winning on what contentions or points – this is shown to the judge through giving a short summary of the voters of the round;

- Asking and answering questions with confidence during cross-ex; and

- Speaking clearly and avoiding mumbling (no matter how fast you are going or how much speaking speed your judge can tolerate) – enunciating is key in a communicative activity!

Types of Judges

There are a few common broad categories or stereotypes of judges – no one should take offense as they’re purely extremes that debaters sometimes refer to. Your judges oftentimes don’t fall into just one of these categories (so don’t talk about your judge being “trad” or “lay” right in front of their faces) – in fact, they may fall into none of them – but in the end, remember to respect all your judges, as they’re putting in much hard work, sacrificing their weekend to help keep debate as a lively activity!

Lay Judges

Lay judges or parent judges are often new to debate as a whole and are still learning the fundamentals (hence many of them being parent volunteers). Despite some debaters’ negative views surrounding lay judges, everyone has to start somewhere – debaters should treat everyone with respect! Lay judges mostly don’t flow speeches line-by-line, and know a moderate amount about world issues, but may factor in various personal biases more often regarding philosophy and politics (something to be aware of). Because many tend to focus on presentation style rather than the content of arguments, ways to appeal include being assertive during cross-ex, making intuitive and simple-to-understand contentions, showing emotion and fluency while speaking (practice your constructive speeches and make eye contact!), and trying to win the overall big picture rather than the line-by-line flow.

An important part of giving the 2NR and 2AR rebuttals is highlighting the big picture summary and voters/voting issues of the round, e.g. how you link better to preventing climate change, or outweigh with conventional war compared to your opponent’s extinction-level pandemic. To win in front of a lay judge (or any judge in general), it is vital to summarize the debate and explicitly list reasons why you won.

Additionally, DO NOT run any progressive arguments in front of them, such as kritiks (a challenge of the assumptions of your opponent, e.g. saying, “the U.S. government is capitalist and therefore bad”), counterplans (an alternative course of action to the affirmative that avoids certain harms), or theory (arguments attempting to change the rules of debate). (these terms will be explained in later lessons, but for now that’s all you need to know about kritiks, counterplans, and theory)

Traditional Judges

Traditional (trad) judges are usually coaches or former debaters who debated LD multiple decades ago, experiencing more grounded logic and stricter norms. Therefore, if the link to your extinction impact isn’t the most obvious, don’t run the contention (sorry nuke war debaters). Oftentimes, going with a structural violence framework and impact (e.g. poverty, racism, oppression); a highly-probable utilitarian one (e.g. climate change on a fossil fuels topic, or conventional/non-nuclear war on an international relations topic); or a more intuitive philosophical framework (e.g. Kant, Locke, Rawls – explained in later units) is a better strategy. Usually, traditional judges also emphasize clarity, a moderate to quicker speed of speaking, and giving voters – but they likely will be flowing, hence evaluate the line-by-line more than parent judges.

DO NOT run progressive arguments – no kritiks, counterplans, or theory – since these were a result of a “progressification” and majorly controversial changing of Lincoln-Douglas debate.

Flay Judges

Flay judges are (simply put) a combination of lay judging and flow judging – usually parents that have understood much of the ins and outs of debate, or former debaters that have graduated high school recently. The line-by-line debate matters more (but never lose sight of the overall picture either), as most flay judges actively flow the round. Running progressive arguments is sometimes okay, if explained in concise terms, connected to real examples, and presented at a medium to quick rate of talking.

Progressive Judges

Progressive (prog) judges or flow judges are oftentimes coaches or recently graduated high school debaters who understand progressive arguments and can handle an extremely fast rate of speaking (given that it is clear and well-enunciated) – sometimes up to 300 words per minute. Running almost any type of argument is ok, as long as you explain the links thoroughly and have evidence to back up your claims. Progressive judges can often make accurate decisions without voters presented at the end, but summarizing the key issues of the round in a few sentences can still be helpful in very close rounds, so that the judge knows what to evaluate.

In General…

Overall, try to read through the entirety of your judge’s paradigm for accurate understanding! You can get a vague idea of how your judge fits into this pseudo-spectrum based on clues in their paradigm. For example, some beginner judges will humbly indicate their lack of participation in judging, or may not even have a paradigm in the first place. Meanwhile, experienced judges usually list their qualifications or summarize their history with debate. Progressive judges frequently will include specific paradigm details about progressive arguments, such as theory, kritiks (“K”s), and counterplans (“CP”s).

Additionally, make sure to pay attention to how they have judged in the past if this is not your first time being judged by a particular judge. And lastly, take notes for future improvement and to better adapt to the judge for later rounds. Their reason for decision (RFD), or their end-of-round feedback, can provide much insight as to how they evaluated your specific round and how they tend to evaluate debates in general – so take notes on what your judge says after the debate!

Adapting to a Panel of Judges

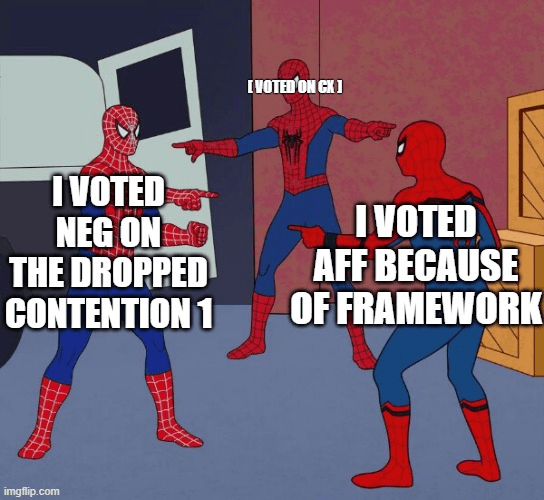

Adapting to one judge may seem hard enough, but wait until you hear about debating in front of a group of judges – also known as a panel! Oftentimes in late elimination rounds at tournaments, you will be faced with the task of debating in front of multiple judges (commonly a panel of 3 judges; but very rarely 2, 5, or even upwards to 9 – like at the finals round of NSDA Nationals!). Overall, panel adaptation is a useful skill to master.

- In the case of all three judges sharing a certain philosophy or type of judging, this can make your job as a debater easier – appealing to one means the others might vote for you.

- When there are two similar judges and one quite different in paradigm, such as two progressive and one lay judge, debaters usually try to win the votes of the two judges with similar paradigms. But if you’re not very confident in doing so, slowing down to explain for the one lay judge [in the example] could prove beneficial in some circumstances.

- Lastly, if every single judge is vastly different in philosophy, your first instinct should be to try to find whatever little common ground you think they would all vote on. For example: if you have one progressive, one traditional, and one flay judge, you might just go for more traditional argumentation at a slightly quicker rate of speaking, ensuring that more judges can follow along with your case.

As a general rule: remember that on a panel of 3, you only need to ensure 2 judges’ votes to win! Juggling with the paradigms of multiple judges can be quite tricky, but in the end, a lot of skill development comes with experience in dealing with panels. The more rounds you win and lose, especially ones involving a panel, the more you get the hang of judge adaptation and coming up with the best strategy to win your judges’ votes!

In this case, all of them on this panel of 3 have quite valid reasons [MAYBE except for the one who voted solely off of CX…]