It’s CX time! Poke holes in your opponent’s case while making witty responses to their questions – simple enough, right? Not really: there are still a few useful things to know before you jump straight into the tension-filled chaos that is cross-examination.

What is cross-examination again? As a brief reminder, cross-ex or CX is a 3-minute period right after a constructive speech, where one debater asks the other a series of questions. The debater that just finished reading their speech would be the one questioned: for example, after the 1AC, the Neg would interrogate the Aff regarding their framework and contentions, and also try to ask clarifying questions. Meanwhile, the Aff in this example would try their best to uphold the position they are advocating for and not reveal too much about the strategy they are going for in the round, all while simultaneously answering their opponent’s questions respectfully and sufficiently.

As there may be quite a bit to unpack in CX, let’s look at it from two perspectives – questioning and answering.

Tips for Questioning

If you’re the debater who is asking in CX, you want to use your 3 minutes to serve two important purposes: for you to clarify parts of your opponent’s case and to try to poke holes in their arguments.

First and foremost, clarify anything that’s genuinely confusing to you. Whether it’s asking how your opponent defined a specific term in the resolution, or being confused about a vague concept they were talking about in contention 2, it’s important to make sure you generally understand what their case is talking about. Remember that you only have these 3 minutes to clear up any confusion you may have, or else you might be stuck clueless for the rest of the round. Prioritize important clarifying questions over immediately trying to dismantle your opponent’s case.

Afterwards, you should spend the rest of your time asking questions to undermine your opponent. This comes in the form of lines of questioning that aim to trap your opponent or make them accidentally/begrudgingly agree to things that would help you (called “concessions“). The general approach of a line of questioning would include asking a sequence of small and specific questions that have an overall objective to them.

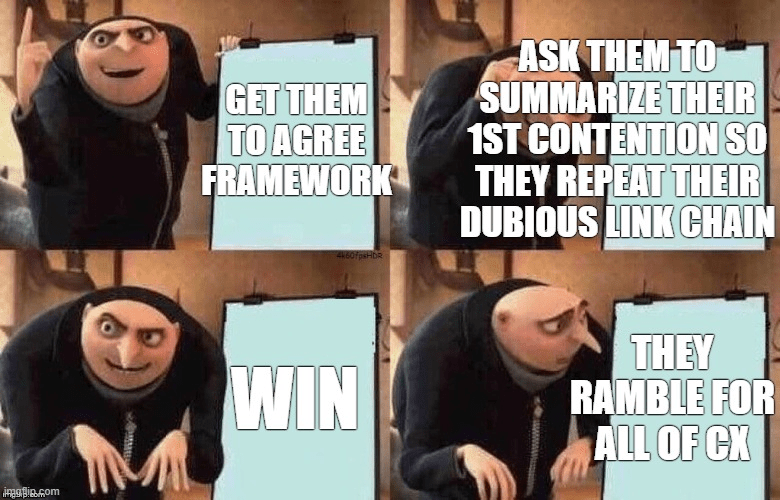

For example, if you wanted to get them to agree that climate change was the biggest impact of the round via impact weighing, you wouldn’t want to start by asking “do you think climate change is the biggest impact of the round?” If your opponent was going with a nuke war impact that focused more on severity/magnitude rather than its likelihood/probability, they would directly say no to the vague and obviously targeted question – you wouldn’t gain any advantage out of it. Instead:

You could then ask “if I dropped my pen right now onto the ground, would that cause a global pandemic?”

– They would probably be confused as to your question and say no.

You could then ask “then should we prioritize preventing me from dropping this pen to stop a global pandemic?”

– They would likely say no.

You would then continue, “so should we value actions less under util if they aren’t likely to impact pain or pleasure?”

– If your opponent agrees to this, then you could utilize the concession in your next speech and try to outweigh them with climate change’s high probability being more important than any sort of magnitude of nuclear war.

Continuing, you could ask: “your case says that economic collapse leads to nuke war, correct?”

– They would say yes.

You could follow up with “have we seen in recent history that countries started immediately exchanging nukes when the economy went down?”

– Your opponent would either say yes or probably would try to wiggle out of the question, but you could easily refute with the fact that there really hasn’t been any example of an all-out nuke war actually happening because of economic downturn (worst cases, a] WW2 Japan was a one-sided nuking and b] the Cold War was eventually resolved). This could further drive in the fact that nuclear war is improbable, hence helping you try to win off of probability.

In summary, to get concessions, start by asking the obvious, then slowly and gradually progress towards making them agree to something that would hugely benefit you.

Aside from clarifications and getting concessions, remember to also use up all of your CX time – don’t end it early. This is the only time in the debate to directly interrogate and discuss with your opponent, in order to get some fatal concessions for an easier win, look good in front of the judge, and/or clarify important things. Many debaters go through the mistake of ending CX early because they run out of questions. To address this, firstly break down your big questions into multiple smaller ones to ask one by one – this helps lead your opponent unexpectedly into a trap you can set up. Secondly, you should be prepared most of the time going into CX with at least one question to ask at the start, then come up with more as you go depending on your opponent’s responses. Finally, in the worst case scenario (especially for new debaters), ask whatever comes to your mind about the debate, no matter how “simple” or “dumb” you may think it sounds – this is important for improving in the future and gaining more experience in CX to do better over time, experimenting with asking different types of questions as opposed to not asking any at all.

Make sure to be fully engaged the whole time as well. Do not organize your rebuttal blocks or write down responses while asking questions in CX – you won’t be able to focus and will look perceptually bad. Passively participating in CX tells your opponent (but more importantly, your judge) that you aren’t paying attention and don’t have much respect for people in the room.

Remember most importantly: this is your CX, and you’re ultimately in charge of what questions are asked. Don’t let your opponent keep rambling on and on for 2 minutes before they decide to stop – if you think their answers aren’t getting anywhere productive for you, you may politely cut them off by saying something like “alright, then what do you think about [xyz question]?” or “that’s fine, next question…” Basically, be respectful, but still be assertive when you need to.

To keep your opponent from stalling for time or re-explaining their entire case, another strategy to keep CX under control for your benefit is starting questions with “could you explain briefly…” or “in 2 sentences…” Some debaters try to stall in CX by repeating their case or talking continuously without end – make sure you’re in control of the 3 minutes when you’re asking questions.

Tips for Answering

Know your position going into cross-examination – you don’t want your opponent to be more knowledgeable about your own case than you. Make sure you aren’t reading a random document you got from another debater or off the internet without first trying to understand what your position is talking about. Basically, the best way to be prepared to answer questions about your case is to know your case. This means reading through it multiple times, taking notes on the link story / each card, and thinking of strategies before the round when you are preparing the topic.

As well, try to answer naturally. Don’t get flustered. This seems like vague advice, but usually you improve with these over time with experience, as you slowly develop a feel for the way CX plays out.

Another issue that may arise is interruptions by your opponent. If they politely interrupt you when you are giving an answer, usually you can let them ask their next questions. But if they are regularly, immediately, or purposefully interrupting you to be rude (which often may be hard to tell), you should respectfully tell them that you are still trying to answer their question – which is commonly understandable. CX can sometimes get out of hand, but it’s important to keep your cool even if you feel your opponent may not be: firstly because you might have misjudged them for being rude, and secondly, even if they are, keeping a level of professionalism can make you look a lot better than your opponent in the eyes of the judge – whose opinion or favoritism ultimately decides the round result.

General CX Tips

Another important aspect of CX is maintaining eye contact with your judge and the judge only. This unspoken rule is also dependent upon the customs of the specific circuit or area that you are debating in, but mostly is true in front of judges who are coaches or former debaters themselves. To make sure you’re safe, you could ask the judge what they prefer at the beginning of CX or the round.

One of the main ideas of cross-ex is perceptual dominance, which refers to the way you present yourself in CX. Being confident, responding quickly, and not fidgeting or showing nervousness helps boost your credibility in front of your judge. Seeming very professional even though you don’t completely know what you’re saying can still go a long way in terms of the round (though it’s not the best idea to be underprepared for CX and the debate). Because most judges don’t take notes on / flow CX, it’s important to give them an overall vibe of being powerful and confident.

But of course, you can’t be completely unaware of what is going on, because anything you say in CX can be used against you during the rest of the round. This is the notion of how cross-examination is binding. Whatever you reveal about your case, evidence, strategy, etc can be brought up by your opponent in their next speeches to win the round with, so don’t make fatal concessions if you don’t need to. The same goes visa versa – you can fully exploit weaknesses your opponent reveals in CX to win.